The 100-million-year evolution of our continent

GNS scientists have produced brand new maps of the continent of Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia showing how the shape of our islands have developed over millions of years.

15 new maps were produced as part of GNS Science’s ongoing exploration of the continent of Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia and show that new discoveries are there to be made.

Aotearoa New Zealand sits on top of Earth’s 8th continent, called Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia

Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia is the world's 8th and smallest continent. It is six times bigger than Madagascar, and about the same area as greater India. Today, the continent is mostly underwater, but it was once a part of Gondwana, and it has even been geologically linked to the ancient supercontinent of Rodinia.

Evidence for the continent had been building over many decades before GNS Science-led research over the last few years put the continent of Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia officially on the world map.

New maps now show the continent taking shape over the last 100 million years

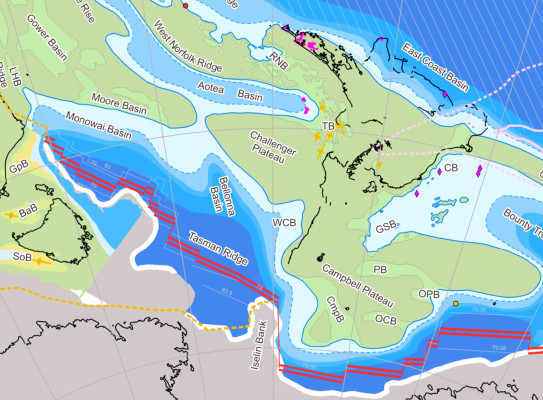

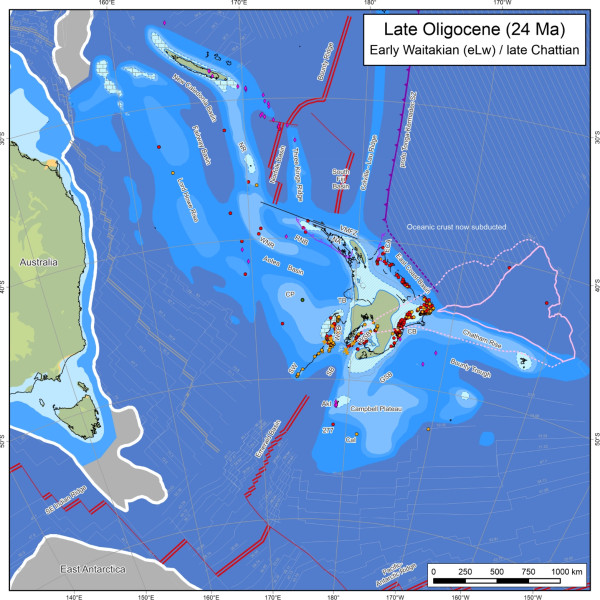

The paper, Palaeogeographic evolution of Zealandia: mid-Cretaceous to present(external link), details the construction of the maps, which span from 98 million years ago to the present day. The maps visualise Te Riu-a-Māui in the correct latitude and longitude and show how we were moving as we split away from the Gondwana supercontinent.

The maps give us a better picture on how big the continent really is. The continent is roughly 4300 km in length, and stretches over about 39° of latitude, and 94% of the continent is currently submerged underwater.

The reconstructions also show just how far we’ve drifted north from polar latitudes in the Cretaceous period. For instance, southernmost Zealandia has climbed from ~80°S to 50°S over the last 100 million years.

Lead author on the paper, GNS Science sedimentologist Dominic Strogen, says these kinds of maps are useful to more than those who study why continents break apart, deform and collide.

“The work is also useful to those studying hazards, both faults and volcanoes, as understanding how these systems have evolved through time is important for understanding how things work at present. Especially in somewhere with an active plate boundary, like Aotearoa New Zealand”.

It’s incredible how far we have come with our understanding about Te Riu-a-Māui, much of which was once almost entirely unknown.

The authors also hope the maps provide a wider geological context for almost everything GNS does and should provide helpful introductory material for people interested in how our continent formed. For the wider geoscience community, the maps will also provide large-scale context for any number of more detailed geological studies.

The maps are also insightful for paleobiologists, who are interested in how species moved into Te Riu-a-Māui from other regions, and then within the continent. We may have a North and South Island now, but that wasn’t always the case and so species would have been able to move more freely when not having to make the journey across Cook Strait.

The geological evidence suggests that the land we now know as Aotearoa New Zealand, was never fully submerged.

The maps have changed beyond all recognition - much like the continent itself

“There were good attempts to make reconstructed paleogeographic maps for much of Te Riu-a-Māui from about 20-25 years ago,” Dominic says. “But these were essentially cartoon in nature, so the maps were drawn very approximately. In the past they would create these kinds of maps by moving paper cut-outs on a light table, new software has become available to allow us to do this digitally, and to bring in far more datasets to constrain the maps.”

“The big step forwards for our maps is the ability to move the blocks that form Zealandia, and all the data that go with them, around in a rigorous and repeatable way. It also allows us to make changes, either to the blocks or to how they move through time and re-draw the maps accordingly, especially as new data become available.”

Dominic says a lot of this data is not new, and the development represents the work of countless geoscientists over the last 150 years, both at GNS Science, its predecessor the New Zealand Geological Survey, and at universities and research institutes throughout New Zealand and around the world. “The more we discover, the more we can add. You can look at tiny parts of this map and identify large or small chunks of work over the years that are represented by more detail within the maps, and also areas where we still don’t know enough and the maps are poorly constrained. Our scientists have contributed across the spectrum to the richness of data types that constrain the maps, from large scale seismic mapping to pollen and microfossils. The total accumulation of our knowledge of the past shapes these maps.”

Knowledge on the formation of Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia will continue to develop

GNS scientists are encouraging feedback from other geoscientists to help improve and refine the models. “The first step to improving upon something is getting it down on the page, for everyone to debate and improve upon.

The more data we input into these models the more interesting they become – some parts we are pretty confident in, but they are just models, and we know they will be wrong in places. Some areas have a lot of data constraining the maps, and some only have a little, but at the end of the day they are our most educated guesses to be improved upon. By putting these maps out there, we are asking the scientific community to help us in finding the holes and plug them, and improve the maps over time.”

-

How were the maps made?

"This work builds on the work, over many years, of numerous colleagues and former colleagues from GNS Science, throughout New Zealand, and around the world, who generated a lot of the primary data used to build the maps,” Dominic says. “This reflects the convergence of many strands of long term and ongoing research projects and 'joining the dots' by staff in GNS Science's Regional Geology, Marine Geoscience, and Petroleum Geoscience departments. Especially influential have been the QMAP 1:250 000 national mapping programme, and research into New Zealand's basement terranes and batholiths, the marine geology of the Tasman Frontier region between New Zealand and New Caledonia, the Chatham Islands and Campbell Plateau, and long term studies into New Zealand's offshore sedimentary basins. International colleagues and research vessels have played an invaluable role in exploring and defining Te Riu-a-Māui."

“But in particular I’d like to thank Peter King and the late Mike Isaac for early inspiration and support for this work, and to Nick Mortimer for highly fruitful tectonic discussions.”

This project was supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) through the Understanding Zealandia/Te Riu-a-Māui (UZTRM) programme.

Co-authors from GNS include Hannu Seebeck and Kyle Bland, and Benjamin Hines and James Crampton of Victoria University of Wellington. -

Is Te Riu-a-Māui Zealandia really the world’s 8th Continent?

On 10 February 2017, the Geological Society of America journal GSA Today published a peer-reviewed, open access science article online called Zealandia: Earth's Hidden Continent. Read it here(external link)

The authors were nine GNS Science staff plus two colleagues from the Geological Survey of New Caledonia and the University of Sydney. The paper had taken many months to write and its origins went back many years to a mix of onshore and offshore GNS Science research projects.

The evidence presented in this paper described 4.9 million square kilometres of the South West Pacific Ocean as underlain by a submerged continent, Zealandia.

The paper showed that Zealandia - like other continents - is large, relatively high, has thick crust, and contains rocks like granite and greywacke. Its continental crust thickness was measured as between 10km and 30km, and increasing to more than 40km under parts of the South Island.

In 2019, GNS Scientist Rose Turnbull, lead authored a paper in Geology(external link). Her findings revealing that the continent of Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia is older than previously thought and we could trace its geological whakapapa back to the ancient supercontinent Rodinia that existed more than 1 billion years ago.

“The isotopic signature of zircon grains from Zealandia tell us that there are ancient 1-billion-year-old rocks still concealed deep in the crust beneath Fiordland and Rakiura/Stewart Island – rocks that were formed as part of the Rodinia supercontinent.

Unfortunately, there is no formal body to approve a continent. As other scientists use Zealandia and cite this research then this validates our work, and the name Zealandia will become more commonly accepted. But it will take time. We hope that Zealandia will eventually make its way onto general world maps, be taught in schools and become as familiar a name as Antarctica.

Read more here(external link).

-

Why is the continent called Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia?

The name Zealandia was first proposed by geophysicist Bruce Luyendyk in 1995 as a collective name for New Zealand, the Chatham Rise, Campbell Plateau, and Lord Howe Rise.

In 2018, GNS Science asked respected Auckland University academic, Associate Professor Mānuka Hēnare, to research and recommend a Māori name that reflected the nature and position of the continent.

Professor Hēnare has 12 years' experience as Associate Dean of Māori and Pacific Development, so he can draw from both perspectives. He was instrumental in naming three ships for the Royal New Zealand Navy (Te Kaha, Te Maru and Te Mana) and is well practised at recommending names that are acceptable across the Pacific.

Te Riu-a-Māui literally means the hills, valleys and plains of Māui - the great East Polynesian ancestor explorer of the Pacific Ocean.

Riu means hull (of a canoe), basin (like the Waikato basin), a belly, the core (of a body). It is the whole that holds the parts together.

Māui is an ancestor of all Polynesians. He sailed and explored the great ocean and caught the fish which he and his crew pulled up. The fish became many of the islands we know today.

The name Te Riu-a-Māui brings together traditional oral narratives and geological science.

-

Our research at GNS Science

Knowledge of our continent, has enduring value. Mātauranga, embodied in part through our databases, samples and collections, informs geological processes that shape Te Riu-a-Māui as well as enriches Māori and Pasifika narratives of exploration and discovery.

We hold more than 150 years of knowledge about Te Riu-a-MāuiWe are proud and dutiful custodians of eight Nationally Significant Collections and Databases that hold foundational knowledge about our continent. Our data supports essential research for building resilience in our communities to natural hazards, unlocking energy and critical mineral resources and developing critical climate change and environmental insights.

Te Riu-a-Māui Zealandia SSIF Programme

GNS Science also leads a geoscience research programme that is investigating and exploring the Earth system structure, evolution, past climate and processes of the 8th continent, Te Riu-a-Māui Zealandia, for the benefit of New Zealanders.