Ambitious plastic pollution reduction needed to stabilise ocean microplastics contamination this century

Research shows global plastic pollution must be cut by at least 5% every year to make progress towards United Nations ‘end plastic pollution’ vision.

Microplastics have been found to be circulating in all of the Earth’s oceans, and levels are increasing. These tiny particles of plastics (less than 5 mm in length) can be hazardous to marine life and make their way from our oceans into human food systems.

A new study from GNS Science and Imperial College London is the first to examine a range of plausible global pollution reduction scenarios, and the impact they would have on ocean microplastic contamination. The researchers used computer modelling to forecast ocean microplastics levels under eight different scenarios of microplastic pollution reduction from 2026 to 2100.

They found that a 5% per year microplastic pollution reduction will stabilise the ocean’s total microplastics load, and reduce concentrations at the surface, but even a reduction of 20% per year would not significantly reduce existing microplastics levels.

GNS Science carbon cycle modeller Karin Kvale says that because microplastics penetrate ocean food webs, they have the potential to persist in our oceans for a long time.

“Biological activity effectively traps microplastics in the upper ocean, where they get passed between plant and animal tissues in an ongoing cycle."

This biological storage of microplastics means that even with pollution reduction, the actual contamination may be incredibly difficult to remove.

The United Nations Environmental Assembly (UNEA) is aiming to adopt a legally binding resolution this year to eradicate the production of plastic pollution from 2040, including ocean microplastics. Kvale and her team hope their analysis will help inform UN negotiations, which are planned throughout the year.

“Our results suggest that to make progress on the UNEA’s draft resolution to ‘end plastic pollution’ in this century, we’ll need to see significant reduction in pollution of at least 5% per year. This is an ambitious target, given plastics production is rapidly increasing,” says Kvale.

Microscopic marine life retains microplastics in surface ocean

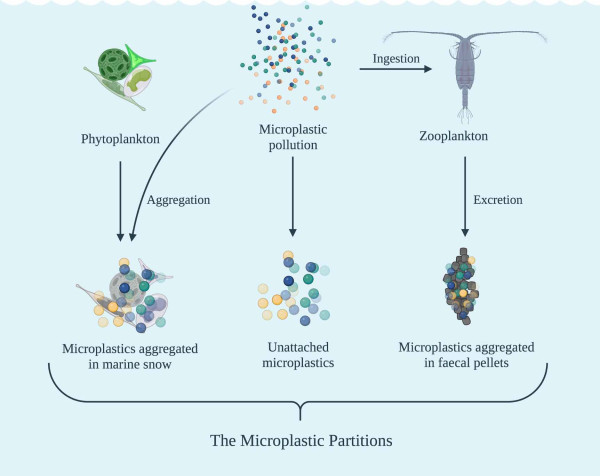

Microplastics pose the greatest threat when they accumulate in the surface ocean, where they are consumed by marine life, including the fish that we eat. They form clumps with the products of other living organisms, either within pellets of faeces from tiny zooplankton, or clustered with the debris of microscopic plants (phytoplankton) known as ‘marine snow’.

These clumps can eventually sink down into the deep ocean, taking the microplastics with them, but the buoyancy of the microplastics can slow their sinking, leaving them nearer the surface.

As marine life holds onto microplastics near the surface, even if the level of pollution produced every year is reduced, there will still be microplastics in the surface ocean for centuries. When the clumps do sink, they will subsequently last in the deeper levels of the ocean for much longer, where their impacts on the ocean food webs are not well known.

“Biology has a potentially huge microplastics storage capacity. This means that clean-up technologies that target plastics litter removal can provide potentially large, long-term benefits to ocean ecosystems, alongside aggressive pollution reduction measures,” says Kvale.

The study found that microplastic contamination down through the ocean’s water column continued to worsen under all the pollution reduction scenarios tested, due to the microplastics already in the ocean and the slow rate of sinking. This suggests that any delays in reducing plastic pollution will carry long-lasting consequences for ocean ecosystem health.

While this persistent microplastic contamination of our deep oceans is a significant concern, we found that even small differences in annual plastic pollution reduction targets can make a big difference to total ocean microplastic concentrations over the coming decades.